Ven Moysh iz geforn: Maurice Schwartz on the Yiddish Theatre in Argentina in 1930 (Part II)

Part I

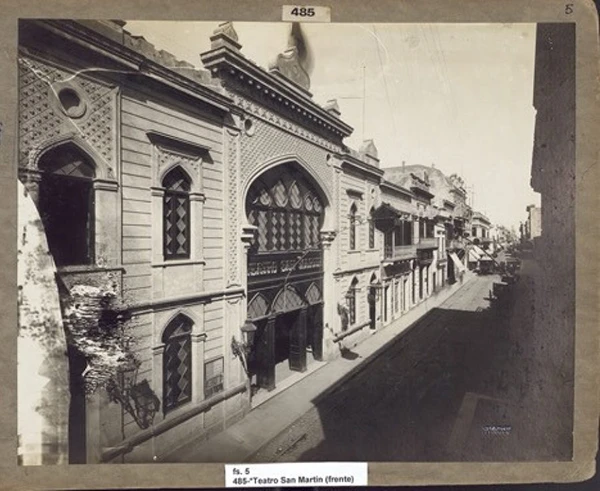

The competition. Schwartz’s Buenos Aires tour coincided with visits by the celebrated Russian bass Fedor Chaliapin (who was singing at the Teatro Colón) and Aleksandr Tairov’s Moscow Chamber Theatre (Moskovskii kamernyi teatr, performing at the Teatro Odeón).

Chaliapin was visiting Buenos Aires after a twenty-two-year absence. He had been “banished” from Argentina, Schwartz related, because he offended opera patrons by showing up half-naked on stage in the role of Mephistopheles. Now, for his ten performances in Mussorgsky’s “Boris Godunov,” he was guaranteed the princely sum of $50,000 (equivalent to about $1 million in 2020). Schwartz claimed that Chaliapin’s presence had a dampening effect on ticket sales at the Yiddish theatre, since Jews who might otherwise have attended some of his own performances “pawned their clothes” in order to purchase expensive tickets at the Teatro Colón. Schwartz’s “green” cousin, for one, thrilled at the opportunity to hear el ruso. Schwartz, however, was unable to attend any of Chaliapin’s performances.

Schwartz did attend a few of the Tairov company’s late afternoon (vermut) performances and offered his thoughts on the Kamernyi teatr briefly in his Forverts travelogue and at greater length in a separate article in Di prese. Most Yiddish guest stars, like Schwartz in 1930, traveled to Buenos Aires on their own or accompanied only by a manager and/or an acting partner.1 In contrast, Tairov’s traveling company comprised fifty-two actors and stagehands, plus sets. This was an extraordinarily expensive tour and evidently the Kamernyi teatr did not come close to covering its costs. “Their success would be much greater if F. I. Chaliapin himself weren’t here,” Schwartz claimed. The language barrier doubtless was an additional factor in holding down attendance at its spectacles; in Buenos Aires “the Spaniards and Italians make do with films,” he wrote, and they weren’t “in a rush to pay three pesos (a little more than a dollar) to see modern Russian theatrical art.” It was left up to the (much smaller) Jewish theatregoing public to cover the “gigantic expenses to bring the troupe here.”

Schwartz saw three of the plays that the Kamernyi teatr put on in Buenos Aires: Alexander Ostrovsky’s The Storm, the nineteenth-century opera bouffe Giroflé-Girofla (with music by Charles Lecocq), and Eugene O’Neill’s Desire under the Elms (all of these were presented in Russian). He was impressed with this “very interesting troupe,” its dedicated and versatile performers, and its modernist productions, which he considered to be along the lines of what might see in a studio for acting.2 Schwartz elaborated on these thoughts in his Di prese article about Tairov’s troupe, where he profiled the company’s leading actors, its salary scales, working conditions, and governance as a cooperative enterprise. Comparisons with conditions in the North American Yiddish theatre were never far from his mind.3

Two other Yiddish stars from New York were visiting Buenos Aires at precisely the same time as Schwartz: Samuel Goldenberg and Stella Adler. They were performing at the Teatro Excelsior, yet their names and that theatre passed completely unmentioned in Schwartz’s travelogues and in other articles penned by him during these months. This, notwithstanding the fact that Goldenberg had shared the stage with Schwartz at the Yiddish Art Theatre the previous autumn and Adler would be do so immediately upon her—and Schwartz’s—return to New York. Schwartz made only the vaguest allusion to the presence of these actors or the existence of another Yiddish troupe in Buenos Aires, when he gently chided the city’s Yiddish newspapers for their (in his view) overly indulgent treatment of shund productions. Goldenberg and Adler were the only other actors mounting Yiddish plays—mostly melodramas, in their case—in Buenos Aires during that period. And, apart from Schwartz’s productions, theirs were the only Yiddish plays being reviewed in the Yiddish and Spanish-Jewish press. Schwartz would have exempted his repertory from the shund epithet, so it was left to the reader to infer that shund plays were being put on by elsewhere in Buenos Aires.

Teatro Colón. The grand opera house of Buenos Aires, the Teatro Colón, is still the most famous theatre in the Argentine capital. Schwartz toured the house during its off-hours, proclaiming it almost as beautiful as the Garnier Opera House in Paris. He was especially impressed by the Colón’s red carpeting, its up-to-date electrical installations, and by the support that it received from the Argentine government – “plus, the theatre also possesses calefacción (steam)!” The Met looked poor by comparison.4

Schwartz and the Yiddish Literati of Buenos Aires

In his Forverts reportage, Schwartz soft-pedaled the frictions prevailing between the Yiddish writers of Argentina—especially the theatre critics for the two rival Yiddish dailies, Jacobo (Yankev) Botoshansky and L. Zhitnitzky, of Di prese, versus Samuel Rollansky (Shmuel Rozhanski), at Di idishe tsaytung. The newspapers covered a post-performance reception that was hosted in Schwartz’s honor by the H. D. Nomberg Yiddish Writers’ Association (June 29, 1930), with toasts, snacks, and speeches lasting practically till dawn.5 (As Mollie Lewis Nouwen has observed, receptions such as this were characteristically male spaces in Buenos Aires.6) “It was my fate to become a ‘peace ambassador’ for a brief time,” Schwartz wrote:

The Yiddish writers of both Yiddish newspapers, the Idishe tsaytung and Di prese don’t dislike one another, but they don’t speak, especially the critics. That is, they don’t intend to inflict any harm, God forbid, but just this: two newspapers, two different orientations.

Here, there is no Café Royal as in New York, to calm the nerves and smooth out the feathers that get ruffled on the Yiddish writers’ shoulders. They encounter one another only in the theatre boxes. They watch the performance and then go their own ways, either to a café or homeward. They can’t even exchange opinions as to the why and the wherefore.

They get offended—not really offended, God forbid, but still, there’s animosity, or as Sholem Aleichem put it, [they’re] tsuhampert [quarrelsome]….

So, the Nomberg Association organized a reception for me, a very heartfelt one. The celebration was very lovely. Of all the banquets that I’ve endured to date, the local celebration was the most festive one….

All of the tsuhamperte came to this celebration, and peace reigned along all of the fronts…7

Nevertheless, the animosities between the rival papers’ critics were profound, bitter, and enduring. The reception was merely a momentary cease-fire in an ongoing “war.”

The Provinces and Moisés Ville

While the vast majority of Argentina’s Jews resided in Buenos Aires, there were sizable communities in the country’s smaller cities and in the agricultural colonies that had been established by Baron Maurice de Hirsch and the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA). After completing their engagements in Buenos Aires most Yiddish guest stars toured cities and agricultural colonies outside of the Argentine capital, and Schwartz was no exception. He performed in the cities of Santa Fé, Rosario, and Córdoba, and in the Moisés Ville colony. Schwartz devoted two installments of his Forverts travelogue to his tour of the provinces, where he discussed only the first and last of these localities. In these articles he concentrated mainly on social and economic conditions and described some of the colorful characters that he encountered along the way. He supplemented the Forverts series with two more articles for Der shpigl.

“The Yiddish theatre in Argentina is a hotel with a large office [providing] transit visas” for the overseas stars, Rollansky once observed. The impresarios offered ship passage and suitable accommodations, along with a percentage of the box-office take.8 Maurice Schwartz was a beneficiary of this “hospitality”: while the other members of his traveling troupe made the overnight train journey to Santa Fé in the overcrowded second-class carriages, he traveled in the comparative comfort and privacy of a first-class compartment.

The second-class carriage was suitable for transporting chickens, not people, Schwartz complained. It contained upright seats for forty passengers, but in reality, between seventy and eighty passengers crammed into the car carrying the troupe’s twenty members. There the actors were joined by gauchos, “a couple of Gypsies,” and Jewish and Ukrainian immigrants. Thick smoke—a blend of Russian makhorka and Argentine tobacco—pervaded the car. “The tuml is like a steam bath Erev Shabbos.” Although the railroads were owned by English concerns, “even the better carriages are far-far from our third class on the Erie Line,” Schwartz remarked.9

He claimed that he had preferred to join the troupe in second class but instead elected to suppress his “sentiments of humanity” and remain in his compartment. Schwartz spent a restless night, lulled to a fitful sleep by the rocking of the train, tormented by strange dreams about the impresario and members of the traveling troupe. (In one of his nightmares, he imagined a Gypsy sucking the blood of one of the troupe’s actors.) Upon awakening, he found that the other actors had slept just fine; unlike Schwartz, they were acclimated to the discomforts of second-class train travel in Argentina.

The city of Santa Fé numbered 500 Jewish families among its 60,000 inhabitants, Schwartz reported. He was inspired by the young people whom he encountered, and by the evidence of an active Yiddish cultural life there, with books being imported from all over and lectures held in a large hall erected by the Jewish community. Schwartz’s company put on two productions in that auditorium: Shabetai Zvi and God of Vengeance. “Everyone came,” he recounted, but news of a woman’s death caused some families to leave the salón early. “A pity, such a young woman,” the troupe’s impresario lamented. “So much income lost.”

Most of Santa Fé’s Jews were engaged in retail and peddling, Schwartz reported. The city possessed a large port, with 8,000 unionized workers, to whom the local Jewish peddlers “sell clothes, bread, and even graves on the installment plan.” Funerals were a big business with the local Italians, and Schwartz met a Jewish “impresario” of the Italian funeral trade who provided his customers with caskets, white horses, and orchestras in elaborate uniforms.

Accommodations in Santa Fé resembled a Berdichev inn, Schwartz recounted, regaling his readers with amusing anecdotes about the hotel’s owner and its resident bootblack and cobbler. The bootblack was grateful to receive the patronage of the impoverished Yiddish actors of Argentina who visited Santa Fé: “How could it possibly be that actors come to ‘Santa Shmey’ with their shoes intact?” The North American stars who accompanied the troupes were not such welcome customers, the shoemaker complained, because “Americans wear shoes that are intact.” That is a paradoxical indication, he contended, that there is a hole in their hearts. “That’s why I’m a sworn enemy of Americans – who asked you to come here?!”10

Schwartz reserved his only negative comments about an Argentine locality in an article intended solely for local consumption. Rosario was a “theatrically dead city” where the crowd’s indifference to Shabetai Zvi sapped the actors’ energies. Silence reigned in the hall as the curtain was raised and silence reigned again as it was lowered.11 Nor was this public apathy limited to just that single performance; the troupe encountered a similar coldness at its productions of God of Vengeance and Jud Süss in Rosario. Schwartz “was informed that it’s the same at the Spanish theatre” in that city, but this came as scant consolation. His spirits revived only somewhat at the banquet that was held in his honor at the Ateneo. “The guests smiled, did their best to create the appropriate atmosphere for an encounter with the director of a Yiddish art theatre.” But the asado (barbecue) at the banquet “reminded me of the Spanish Inquisition, where flesh was also roasted—Jewish flesh.”12

By contrast, when Schwartz arrived in Córdoba, the sun began to shine – literally and figuratively. He spent three memorable days in that city. The audience was young and cheerful – “this is not Córdoba, Spain.” Every moment was filled with pleasure, he recalled. The audience was enthusiastic, as in New York during the heyday of the Yiddish theatre. “Even the gentiles on stage who changed the decorations were dear gentiles.”13

And finally, there was Moisés Ville, the first and “most important Jewish colony in Argentina” (as the Forverts headline put it), dating back to 1889. Even before Schwartz traveled to Moisés Ville, he sensed the powerful hold that the colonies had on the country’s urban Jewish imagination. In one of his popular songs, the Argentine Yiddish entertainer Jevel Katz extolled Moisés Ville (“Mozesvil,” in Yiddish) as “a yidishe medine, a shtolts far Argentine” (a Jewish state, the pride of Argentina). Schwartz’s dispatch from the colony was very much in that vein.

When the visiting actors arrived at the train station (several miles away from the settlement) they were greeted by representatives of various committees, including the president of the Kadima cultural center, a Dr. Malamut. They were escorted to the colony by one of the oldest colonists, a Señor Langer, who informed them that he had had the honor of greeting the Yiddish writers Peretz Hirschbeyn and Hersh Dovid Nomberg, during their visits to Moisés Ville some years earlier. Theatre performances took place in Kadima’s building, which impressed Schwartz as both beautiful and modern, with a good stage and seats for 600 to 800 spectators.

Although the ostensible purpose of Schwartz’s visit to Moisés Ville was to perform there—and his troupe did put on Shabetai Zvi within hours of arriving—he devoted most of his journalistic attentions to descriptions of the colony’s physical plan and its economic prospects. He spent a total of four days in Moisés Ville, which afforded him the time to meet many of its residents and absorb the colony’s ambience.

There was no hotel in Moisés Ville, so Schwartz was put up in a bedroom in the courtyard adjoining a coffee house. The locals were very hospitable and thwarted a guest’s boredom by showing him around the colony in their cars. On one such tour, Schwartz was introduced to some of the earliest colonists, their children, and grandchildren. Yiddish was the colony’s lingua franca, except in addressing an Argentine gentile (pundik, in local Yiddish usage); the maids, servants, and the policeman all spoke Yiddish.

In the Forverts, Schwartz observed that there were two drama societies in the colony—the Moisés Ville Drama Society and the Goldfaden Society—each of which put on “dramas and comedies by the best playwrights.”14 The two organizations were evidently ideological rivals. He elaborated upon this elsewhere, expressing his disapproval of the rivalry between drama groups in such a small settlement and advocating their merger into a single, unified organization. “Class politics must not interfere in a drama society,” Schwartz scolded. “Theatre dare not have any Weltpolitik; one polemic should rule: Pure theatre; fairness to every playwright, on the left and on the right, the nationalist [i.e., Zionist] and the opposition. The actor must be neutral.” These were the principles according to which Schwartz guided the Yiddish Art Theatre; however, the New York Yiddish theatre scene was not exempt from political rifts along these very same lines.

Schwartz rhapsodized about cultural life in the settlement: Not only were the Jewish colonists helping to feed the nation and the world, “but they haven’t forgotten that they are a People of the Book and [also] built auditoriums and libraries.” “I have seen Moisés Ville and for that alone my trip to South America was worthwhile,” Schwartz concluded. “It’s been a long time since I heard little children speaking a clear, healthy Yiddish as in Moisés Ville—not pretentiously, as the boast goes, but simply; they speak a natural Yiddish.” This was just one of the localities in Argentina where Schwartz visited community libraries offering reading material from throughout the Yiddish-speaking diaspora. Some of those organizations were also repositories of Yiddish play scripts.15

Schwartz Reflects on His Tour’s Accomplishments

As Schwartz’s stay came to an end, he offered some reflections about what, for him, was the fulfillment of a dream. Beforehand, he had felt some trepidation at the prospect of leading a troupe of “strangers,” after having spent so many years in New York, working with a familiar pool of actors and performing in front of audiences that had become jaded by his repertory and productions. He had grown “tired already of performing each season in a new theatre in a new neighborhood [in New York], by being bothered to sing into records in order to pay the enormous rent for theatres.”16 In Buenos Aires, he encountered a new and enthusiastic audience, and new critics as well: Jewish, Spanish, and German. The theatres were mobbed as in the days of “Kessler-Adler-Mogulesko”—when $700 a week wasn’t required for ‘artistic satisfaction’.”

He accurately foresaw that Buenos Aires would occupy a very important position in the Yiddish theatre world, but also expressed the view that the ranks of performers there required better and more serious acting talent. As well, its newspapers needed to offer stronger criticism of the melodramas and operettas that were being put on. His own performances “confirmed the fact” that there was an audience in Buenos Aires for the “better,” more literary plays. Finally, his experience in Buenos Aires persuaded him that he ought to travel around and teach his repertory to actors everywhere, and not just in New York City. That would vindicate his twelve years of work with the Yiddish Art Theatre.17

In practice, Schwartz did travel more during the following three decades, including numerous trips to South America—and Buenos Aires became one of the last redoubts of the “better” Yiddish repertory. This was true both in terms of the other guest actors that traveled there (especially Jacob Ben-Ami, Joseph Buloff, and Luba Kadison) and with respect to local developments—in particular, the independent, leftist Teatro IFT (Idisher folks-teater), which flourished from the mid-1930s into the mid-1950s, when it shifted to performing in Spanish.18

Notes

- In 1933, Schwartz would return to Buenos Aires, together with half a dozen actors plus supporting crew from the Yiddish Art Theatre. During that tour the company staged its greatest hit, Yoshe Kalb, adapted from the novel by Israel Joshua Singer.

- Maurice Schwartz, “Oyf di gasen un in di teaters fun Buenos Ayres,” Forverts, August 28, 1930. Unfortunately, Schwartz missed the Tairov company’s production—one of the earliest, outside of Germany—of The Threepenny Opera, by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill.

- “Moris Shvarts vegn Tairovs trupe: fun a briv tsum ‘Forverts’,” Di prese, October 3, 1930. I have been unable to locate this article in the Forverts, in a survey (via the Historical Jewish Press Project / JPress) of issues of that newspaper from the months of August and September 1930.

- Maurice Schwartz, “Moris Shvarts bashraybt zayne letste forshtelungen in Buenos Ayres,” Forverts, September 4, 1930.

- “Der hartsiker kaboles ponem fun ‘Nomberg shrayber fareyn’ far Moris Shvarts,” Di prese, July 1, 1930.

- Molly Lewis Nouwen, Oy, My Buenos Aires: Jewish Immigrants and the Creation of Argentine National Identity (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2013), 99–101.

- Maurice Schwartz, “Stsenes un bilder fun idishen leben in Buenos Ayres,” Forverts, August 2, 1930.

- Samuel Rollansky [Shmuel Rozhanski], “Dos idishe gedrukte vort un teater in Argentine,” in Yoyvl-bukh: sakh-haklen fun 50 yohr idish leben in Argentine; lekoved “Di Idishe tsaytung” tsu ihr 25-yohrigen yubileum (Cincuenta años de vida judía en la Argentina: homenaje a “El Diario Israelita” en su vigesimoquinto aniversario) (Buenos Aires: 1940), 412, 415. Rollansky’s essay was subsequently published as a monograph, under the title Dos yidishe gedrukte vort un teater in Argentine (Buenos Aires: 1941).

- The Erie Railroad was not considered one of the premier passenger lines during the heyday of American train travel.

- Maurice Schwartz, “Moris Shvarts shildert stsenes un bilder in di shtetlach fun Argentine,” Forverts, September 27, 1930.

- This was not the first time that Schwartz had encountered an audience that didn’t applaud, but at least in the other cities where this had occurred—such as St. Paul, Minnesota—“the entire audience, to the last person, waited for the actors at the entrance to the stage.” Not so in Rosario, however.

- Maurice Schwartz, “Ayndrukn fun idishn lebn in Argentine,” Der shpigl, October 16, 1930.

- Maurice Schwartz, “Ayndrukn fun idishn lebn in Argentine,” Der shpigl, October 23, 1930.

- Maurice Schwartz, “Mozesvil, di vikhtigste idishe kolonye in Argentine,” Forverts, October 11, 1930.

- Maurice Schwartz, “Ayndrukn fun idishn lebn in Argentine,” Der shpigl, October 23, 1930. In August 2019, during a cursory examination of a box of play scripts in the Fundación IWO’s archives in Buenos Aires, I came across a fair number containing ownership stamps indicating that they had once belonged to cultural organizations in Argentine Jewish agricultural colonies.

- During his visit, Yiddish newspapers in Buenos Aires carried advertisements for Schwartz’s recording of the humorous monologue “A Drunken Cantor” (“A khazn a shiker”).

- Maurice Schwartz, “Moris Shvarts bashraybt zayne letste forshtelungen in Buenos Ayres,” Forverts, September 4, 1930.

- For background on the Idisher folks-teater—Teatro IFT, see Karina Wainschenker, Antecedentes, surgimiento y desarrollo del teatro IFT (Buenos Aires: VII jornadas de Jóvenes Investigadores, Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2013) accessible online at https://www.aacademica.org/000-076/338; Paula Ansaldo, “El teatro como escuela para adultos: un recorrido por la historia del IFT en su tránsito del ídish al español,” in Teatro ídish argentine, eds. Susana Skura and Silvia Glocer,(Argentiner yidish-teater) (Buenos Aires: Editorial de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2016), 143–160. Accessible online at http://publicaciones.filo.uba.ar/sites/publicaciones.filo.uba.ar/files/Teatro%20%C3%ADdish%20argentino%20%281930-1950%29_interactivo_0.pdf.

Article Author(s)