Current issues related to planning that our faculty and students are thinking about, participating in, working on . . .

By Nancy Frank

Anyone who has ever taken a course in urban planning knows that protecting public health, safety and welfare is the foundation for many planning efforts. Historically, planners proposed zoning laws to keep dangerous land uses from locating near residentials areas. In recent years, the planning profession rediscovered its public health roots, partnering with public health organizations to promote healthier lifestyles—designing communities for active living and encouraging urban agriculture to promote healthy eating.

Ironically, when planners work with communities that identify safety from gun violence as a critical neighborhood need, planners often feel helpless. Our most common approaches and tools are inadequate and inapplicable. Planners propose building up the physical and human capital of these neighborhoods to reduce risks of violent crime. And such efforts make a difference, but only over many years of effort and investment. Planners often view more immediate solutions as the province of policing, not planning.

Sometimes, as planners, we need to learn from those we serve. As a planning faculty member, I teach my students to value public participation in planning because planners learn valuable things from this engagement. Members of the community come up with solutions to problems that would not occur to the professional planner.

The story below, about one organization’s determination to do something about gun violence, is just such an example. WestCare Wisconsin, a non-profit health and human services agency, carried out a 10-month campaign to reduce the risks from guns in Milwaukee’s Harambee neighborhood where WestCare works. As a result, 877 gun locks were distributed to households, greatly reducing the likelihood that those weapons would be stolen and used in crimes, reducing the likelihood that those guns would be used by another member of the household to commit suicide, and reducing the risk of accidental firing of the gun by children in the household. Research from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that “from 2005 to 2014, roughly 20,000 American minors were killed or seriously injured in accidental shootings; the majority of those killed in these tragic accidents were aged 12 or younger” (Giffords Law Center 2018). Moreover, two-thirds of gun deaths are suicides.

Planners need to remind ourselves that despite media-fueled stereotypes of violent neighborhoods, gun violence is a public health issue not solely a criminal justice issue. Second, planners need to engage in community efforts to reduce gun violence, because promoting strong community connections builds community resilience and helps communities mobilize against gun violence.

The work by WestCare Wisconsin in Harambee is described below by WestCare’s executive director, Elizabeth Coggs. Planners: we can take a lesson.

Learn more about WestCare on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/pg/WestcareWisconsin/

Sources:

Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, 2017. “Safe Storage,” http://lawcenter.giffords.org/gun-laws/policy-areas/child-consumer-safety/safe-storage/#footnote_1_35003, accessed February 10, 2018.

“Injury Prevention & Control: Data and Statistics,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal_injury_reports.html and http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/nfirates2001.html, accessed May 18, 2016.

“Love Up, Lock It Down” . . . Gun Safety Campaign

By Elizabeth Coggs, WestCare Milwaukee

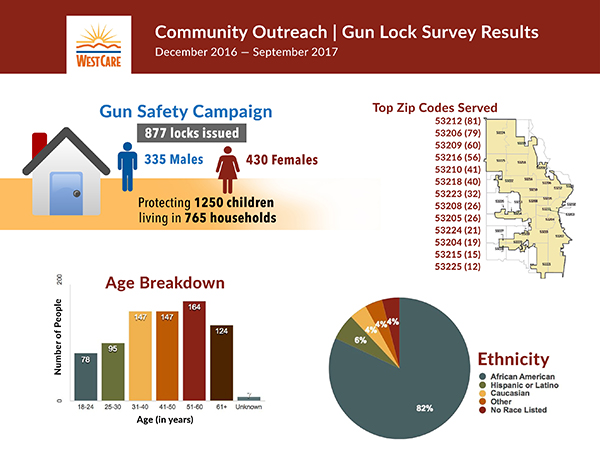

WestCare Wisconsin set up an informational booth throughout the City of Milwaukee (Dec 2016 – Sep 2017) at various community events, big and small. The team along with members of the Youth Action Council were able to provide statistics and violence prevention information including gun locks for seven hundred sixty-five (765) unduplicated residents. Eight hundred seventy-seven (877) gun locks were issued, which included a few households where more than one lock was requested. In addition, some of the locks were issued to those residents who traveled to the Harambee Community Involvement Center office as a result of the community outreach efforts of the youth Street Outreach Team.

Of the 765 residents completing the survey, three hundred thirty-five (335) were Male and four hundred thirty (430) were Female; with the majority being African-American (630). The ethnicity breakdown also included forty-nine Hispanic, twenty-seven White, four Asian-Americans, three Native American, twelve that selected 2 or More Races and eleven who identified with Other. Twenty-nine individuals opted not to identify their culture. A few of the surveys showed that the citizen selected two ethnic choices which were included in the count.

The age range represented seventy-eight (18-24 year old); ninety-five (25-30 year old); one hundred forty-seven (3140 year old); one hundred forty-seven (41-50 year old), one hundred sixty-four (51-60 year old), one hundred three (61-70 year old), seventeen (71-80 year old); and four (81-90 year old). Seven individuals did not list their age range.

City of Milwaukee residents came from twenty-three (23) different zip code areas, with a majority deriving from one of the City’s poverty and crime stricken communities (53212); one Wisconite came from the City of Kenosha (53144); three citizen came from the City of Oak Creek (53154) area, a township within Milwaukee County; two from the adjacent county, the City of Waukesha area (53186); two from Muskego, Wisconsin (53150); one from Pleasant Prairie, WI (53142), a municipality 38 miles south of Milwaukee, in Kenosha County; and one from Packer country, Green Bay, WI in the Brown County. In addition, we had visitors from different areas of the country including the southeast area of North Dakota (58103); one citizen from Harvey, IL (60426), a municipality in a south suburb of Chicago, in Cook County; one citizen from Carrollton, TX (75006), a municipality 1,003 miles south of Milwaukee.

While offering their name was optional, two hunded eighty (280) citizens provided their name on the survey.

Most importantly, from the inception of the “Love Up, Lock It Down” Gun Safety Campaign (Dec 2016) and throughout the month of September 2017, the number of those completing the survey listed ONE THOUSAND TWO HUNDRED FIFTY (1,250) CHILDREN from their collective households; which encourages our optimism that these precious community gems will be safe in their respective homes from the consequences of the mishandling of a firearm which results in the tremendous pain of losing either one of them or another adult loved one. WestCare Wisconsin is doing our part in trying to curtail urban violence, for it’s better to prevent an unconceivable thing from happening, than it is to try to mend the broken hearts once the unthinkable has happened.

Collective work and responsibility is the impetus behind the success of this movement. The gun safety campaign is a collaboration of community and human service mavens, as well as private and public sector professionals commited to working towards doing something positive to address the gun violence in Milwaukee. This effort would not have been possible without the generous support of Master Lock, City of Milwaukee Office of Violence Prevention and the City of Milwaukee Community Development Block Grant office.

Participant Quotes and Credits

Infographic based on data from Westcare. Designed by MUP student Sadie Baile.

Infographic based on data from Westcare.

Designed by MUP student Sadie Baile.

In spring 2017, Professor Kirk Harris launched a podcast, hosted by Fathers, Families, and Healthy Communities (FFHC), called Chicago Run Down. Professor Harris engages conversation about fathers, families, and the promotion of healthy communities. In Episode 3, posted in December 2017, Ed Davies, the director of Power of Fathers joins us to discuss the work he is conducting in our communities. The Power of Fathers is an innovative collaboration of four agencies, working together for the past two years, to engage fathers more effectively in the healthy development of their children.

You can watch the podcast: https://ffhc.org/podcast/ffhc-the-chicago-rundown-episode-3/

By Nancy Frank, Department of Urban Planning, Chair

I am feeling proud today. I am proud of the small role I played in bringing to the Wisconsin planning community this story about the fight for housing equity. I am proud because Kori Schneider-Peragine (MUP 1997) has been a leader in advocating for affordable housing options in suburban Waukesha County. I am proud of my student editor, Cassandra Leopold, who produced an excellent story, interviewing Kori to understand the planning story behind the headline. And I am proud of the un-named planners in suburban communities and at the regional planning commission, many of them also our alumni, who Kori credits with being supportive of her work and for housing options in their communities.

You can read the story here:

http://us10.campaign-archive2.com/?u=b5827ef04ccfd10d628b54268&id=668d3d83ca&e=6264bad957

By Ryan Peterson and Matt Werderitch

Master of Urban Planning students, UWM

The UWM Office of Sustainability invited us to conduct an evaluation of the campus’s food-purchasing habits. The evaluation included a detailed analysis of policies and purchasing patterns of Restaurant Operations, the campus’s food purchasing agent. An important component of the evaluation was the amount of sustainable and/or locally-sourced food that the campus purchases on an annual basis. The report will help to continue the campus to stay on track in achieving its goal of increasing the proportion of sustainable food options sold in campus food service.

We used the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS) to organize food purchases into categories, allowing comparisons with other institutions. For the first time in the university’s history, UW-Milwaukee achieved the Gold Rating!

You can view the report here

“#BlackLivesMatter” has stimulated a domestic and international discourse that seeks to challenge racial injustice and economic inequality by organizing against it. Issues of racial and economic justice have found resonance in the discourse of America’s 2016 presidential election cycle, while organizations such as the Brookings Institute indicates that economic disparities and inequality pose significant challenges in that they contribute to cycles of poverty, racial injustice, social unrest and political turmoil on a global scale. These are issues I had to grapple with very early in my own life experience as a kid growing-up in the inner city and now grappling with these issues as an adult committed to ensuring America lives up to its democratic promise.

It was the height of the Civil Rights period. In 1967 the social unrest in Newark, New Jersey took place and is forever etched in my memory. I was in elementary school then. School was out and the summer was hot literally and figuratively as the emotions of the most racially oppressed segments of our nation boiled over. The decade of the 1960’s provided witness to the dramatic internal struggle for social and economic justice in America and also gave witness to the deaths of President Kennedy, Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King and brought in sharp relief America’s claims to being the most democratic nation in the world.

That summer I was on an outing with the family at the Dairy Queen in downtown Newark. We were sitting in our old Ford station wagon with holes in the floor boards and wood side panels that were popular in the day waiting for our ice cream cones. Suddenly, I saw my mother bolt for the car without the ice cream cones and we sped from the Dairy Queen and the next thing I saw and heard was a big bottle crashing against the glass of the rear window of the station wagon. My mother said her suspicions were raised by the odd behavior of the Caucasian males who were hanging around the Dairy Queen, which is why she decided to leave so quickly. That day was the first day of a week of unrest in Newark, but Newark was only one of a few places in which unrest was happening. Unknown to me that experience was my introduction into urban planning.

That experience caused me to wonder about a number of things. Why were those men at the Dairy Queen angry enough to throw a bottle at our station wagon? What was at the core of the unrest happening in Newark and other cities? What should cities and their citizens do about the unrest? What should the country do about this tension and anger and where does it come from? These questions lead me to read my first autobiography as an elementary school student which was the autobiography of Malcolm X by Malcolm X and Alex Haley. That book incited my interest in African-American history, government and how these topics intersect in the context of community attitudes and actions. As an undergraduate student I studied African-American history and began to understand how the plight of African-Americans was so inextricably linked to individual attitudes and governmental policies and institutional practices that contradicted the iconic symbol of America as the world’s leading democracy and the home of the “free and the brave.” The exploration of that paradox became the foundation of my personal and intellectual quest. It is why I studied government and public policy at the graduate level and why I decided to go to law school and ultimately became a lawyer.

My first professional position out of law school was serving as a legal service lawyer. I worked with low-income individuals within low-income communities helping them to resolve the daily challenges hoisted upon them as a result of their economically vulnerable conditions and socially precarious status manifested in their lack of housing and employment, the impact of governmental neglect and overreach on them, the limited educational opportunities and the crushing impact of segregation. All of which created a revolving door through my office in which I parsed out micro-level interventions for macro-level issues of racial and economic inequality. I was frustrated because my training as a lawyer had me operating to craft narrow solutions at an individual level while not addressing the intractable systems issues that where located in communities, located in the city at large and located in governmental systems causing the same clients to come back into my office with a different set of issues rising out of the gross injustices they experienced daily and had to live through. I was metaphorically placing a band-aid over gaping wounds of injustice. Troubled by my experience as a legal service lawyer I was on a quest to identify how I could personally and professionally bring together my interest in improving conditions in vulnerable and racially and economically disadvantaged communities, while challenging governmental policies and institutional practices that have generated racial and economic inequality, while also building a vision for what is possible and then have the opportunity to implement that vision. The task that I laid out for myself was enormous and appeared insurmountable.

My wife was working as a researcher at the time of my quest. She was given the opportunity to visit Cornell University to learn more about pursuing doctoral studies in microbiology and food science at Cornell. While she was on campus exploring the program I was left to my own devices, which is always dangerous. I was strolling around the Cornell campus which was very nice that time of year and I walk by a big old architecturally distinct building call Sibley Hall. I was curious so I walked inside. As it turns out, I had found my way to the Architecture Department. Architecture was not totally unfamiliar to me but I knew so little about it. I continued my journey in the building and saw a sign that said Department of City and Regional Planning. I said to myself what the “heck” is city and regional planning, it was something I had never heard about. I looked up on the bulletin board scattered throughout the hallway walls and saw course information about things like neighborhood development, community organizing, the political economy of place, discussion groups on race, gender and class. I was fascinated and excited! Could this be the way I bring together my interest in the history of vulnerable communities, address my concerns related to governmental and institutional policy and practices and their role in replicating racial and economic inequality, and then have a way of acting on these interests in an applied context? As it turns out after having a discussion with students, faculty and graduates of the Cornell City and Regional planning department I felt I found my answer, my niche if you will. Planning is a way of thinking about communities, cities and regions comprehensively and through a multiple disciplinary lens. The planning field embraces the fields of history, politics, economics, sociology, environmental studies, design, and ethnic studies of all kinds only to name a few, and is also committed to creating cities and regions that are racially and socially just that serve everyone. If we look at our cities today whether its Ferguson, MO, Baltimore, MD, Sanford, FL, New York, NY or Oakland, CA, Milwaukee, WI issues of social and economic inequality and injustice remain front and center and not unlike the social unrest that I witness in 1967 change is being demanded in those cities.

My commitment as an academic and as a practicing urban planner focused on social planning is to respond to the demand for change. At the core of planning practice is the idea of advancing a democratic commitment that lessens the paradox that is America, which is what took me on my journey and lead to my discovery of urban planning. Urban planning provides us with a vehicle that allows us to envision a “just world” and act to create that world in ways that are hands-on, meaningful and purposeful.

There are many thinkers and practitioners out there with compelling stories and a passion for planning “socially just” cities. Check out the link and get to know them.