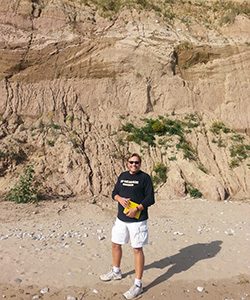

It’s a warm Thursday morning in Cudahy under a bright autumn sky. Waves on Lake Michigan are lapping at the shore, and a breeze rustles the trees atop the 90-foot bluffs bordering the lake. It’d be quiet and peaceful, if not for the drilling rig boring into the earth collecting samples for Mark Borucki’s PhD dissertation.

Borucki is a lecturer in the Geosciences department who is also completing his doctoral degree at UWM. He’s studying how Lake Michigan and the bluffs along the lakeshore were formed. By drilling down into the bluffs and examining the stratigraphy he uncovers, he should be able to put together a detailed history of glacial activity in the Milwaukee area over the last 50,000 years.

“Others have examined the bluff stratigraphy before, but not to the degree that I’m going to do it,” Borucki said. “This drilling, no one has ever done that. You can walk the beach, but you don’t know what’s down below.”

The drill bores into the ground and drives a hollow metal tube into the soil. When that tube is brought back up, it contains a samples of deposits not exposed in the bluffs.

Borucki worked with Frank Miller, the superintendent of the Cudahy Water Utility, to obtain permission to drill on city property at the base of the bluffs. The drilling location abuts Cudahy’s water pumping station, which draws water from Lake Michigan and pumps it to the city’s water plant. Miller provided geotechnical logs for borings that were done prior to the construction of the pump building, which allowed Borucki to see what glacial units were present beneath the beach. The logs were interesting, but no soil samples were available for analysis.

If you look at the bluffs and the layers exposed in them, you begin to get an idea of what was happening when a massive glacial lobe filled the Lake Michigan basin.

“We have a river out in front of the ice, and the pinkish brown layer is glacial till,” Borucki said, pointing out layers in the bluff.

“Glacial till is unsorted and not layered,” he added. “If you can imagine, glaciers can move the Sandburg dorms, no problem. Water only has so much energy, so it will transmit sand grains, gravel and sometimes cobbles. It takes a lot of energy to move those cobbles and boulders with water. We know we have river deposits overlying that till.”

The layers in the eroded and denuded bluffs indicate there were probably lakes in front of the incoming glaciers at one time. The units exposed in the bluffs confirm that Milwaukee was a dynamic geological environment, with glaciers flowing westward and then melting back probably dozens of times during the Pleistocene Epoch, which extends to about 2.6 million years ago. There were also wetland areas present at the drilling location at one point, based on the presence of dense chunks of peat, tightly compressed organic compounds that are so old that carbon dating can’t accurately estimate their age.

What’s below the exposed bluffs is anybody’s guess, and Borucki’s research will shine a light on how the ground beneath our feet was formed. It’s important because that ground isn’t always stable and the bluffs along the lake are eroding in some locations.

“Perhaps other researchers will be able to use the collected data to better characterize bluff retreat and recommend means of minimizing it,” Borucki said. “In some areas like Kenosha and other areas around Milwaukee, people wanted that view, so they just said, we’ll build a home right here. Perhaps they should have consulted a geologist first.”

It will be a while before Borucki can fully analyze the data recovered from the drilling, but when he does, he’ll be able to paint a clearer picture of how the landscape came to be.