On a chilly spring afternoon, field biologist Gary Casper and assistant Beth Mittemaier, both in waders, slogged through a marsh just off the Good Hope Road exit on Interstate 41 to reach submerged metal traps. The first was empty, but the next trap held a blue-spotted salamander coiled in the bottom.

“So far, this is the only species we’ve found here,” Casper said as he tipped the creature into his hand.

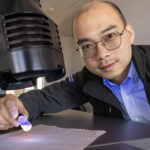

Casper, a biologist with the UWM Field Station, is in charge of conducting the first-ever comprehensive wildlife survey in Milwaukee County. The survey is one step toward restoring the quality of the Milwaukee Estuary and its associated rivers, which were designated an “Area of Concern” in 1987 by the Environmental Protection Agency and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Casper’s survey will show how wildlife has been affected by pollution and development in the area.

“Some things clearly are gone. There used to be wolves in Milwaukee County, but now we’re not going to spend any time looking for them,” Casper said. “But other things, like the prairie crayfish — that was listed as ‘special concern.’ Now, as a result of our work, we found that they’re very widespread and common, so it’s possible that that ranking was in error and they’re not really of concern.”

Finding these animals takes some legwork. Casper and his team have set traps to catch turtles, crayfish and salamanders. They’ve put out trail cameras to record larger mammals such as otters and foxes. They have even set up digital audio recorders to capture and analyze the sounds of animals like birds and frogs. The sights and sounds give the team a good idea of how many animals, and what types, live in a given area.

Some of Casper’s findings were unexpected.

“I think the Virginia rail we got last year breeding in a marsh was a surprise. All of the professional birders we consulted said, ‘Don’t bother looking for them; they’re not here,’” he said. “I was happy to find a couple more populations of digger crayfish, but they’re definitely rare. The fact that they’re surviving in urban Milwaukee County is encouraging. We were happy to find that flying squirrels are hanging on even though there’s not a lot left in terms of good, quality, mature forest.”

But there were also surprises in what Casper’s team has not found, such as most salamanders, and a lot of small frogs such as spring peepers and tree frogs.

The next step is to identify how to help some of those threatened species recover in Milwaukee County, then procure funding and begin restoring some habitats. After that, Casper said, wildlife surveys should continue to measure the success of the restoration projects.

One of the most hopeful and inspiring signs, Casper said, is how involved the community has been.

“Really, all conservation is local. What we’re looking at is literally what’s in your backyard,” he said. “It’s what your kids are able to see and play with. Are they able to go catch frogs? Are they able to see some of these really pretty birds, like redstarts raising young in the neighborhood woodlot?

“A lot of people warn me that ‘People don’t care about those slimy frogs,’” Casper continued, “but I’ve found the opposite is true. Once they understand what’s going on, it’s not just pretty birds and warm and fuzzy mammals they care about; they care about it all.”

Community members can help Casper with the survey by reporting their own wildlife sightings at iNaturalist.org.