When Ruth Etzel practiced pediatrics in North Carolina in the 1980s, she saw many children who came to the clinic with pneumonia, bronchiolitis and coughs. The parents of most of the children smoked, and she became interested in the possible link between parental smoking and children’s lung diseases.

“That was before we understood the harm caused by secondhand smoke,” says Etzel, now professor of epidemiology in UWM’s Joseph J. Zilber School of Public Health.

As a result of her interest, she performed the first study documenting that children with secondhand exposure to tobacco smoke had measurable nicotine and cotinine, another alkaloid found in tobacco, in their bodies.

That early experience inspired her to pursue a career studying the environmental hazards impacting children. “They are so vulnerable, and don’t have much control over what they are exposed to in their homes and neighborhoods,” says Etzel, who also is director of the Integrative Health Sciences Facility at the Children’s Environmental Health Sciences Core Center.

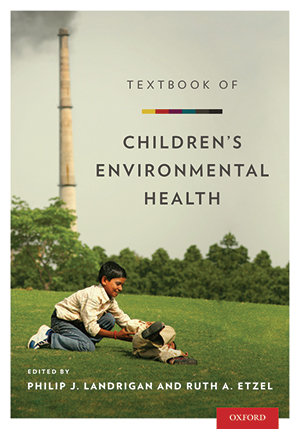

Etzel is co-editor of a new book, “Textbook of Children’s Environmental Health,” that focuses on the new and growing field. The book is written in down-to-earth language, and aimed at students in schools of public health, health care professionals and families, she says.

The goal of the book is to summarize what researchers know about the risks from contaminants in the environment and help translate current scientific research into preventive strategies. Etzel is the author or co-author of six chapters of the 60 chapters in the book.

New chemicals, greater risks

As Etzel and her co-editor, Philip J. Landrigan, note in the book’s introduction, the prevalence of autism, asthma, ADHD, obesity, diabetes and birth defects has grown substantially in the last four decades. In the same period, more than 80,000 new chemicals have been developed and released into the environment. The World Health Organization attributes 36 percent of all childhood deaths to environmental causes, according to the authors.

The book looks at how environmental exposures in early life – chemical, nutritional and social – influence health and development in children and throughout the life span. Chapters look at the environments children live in, the hazards in those environments, the links between environment and disease, and the prevention and control of diseases linked to the environment.

Etzel brings extensive experience in the field to her work on this book. She spent 20 years as a commissioned officer in the U.S. Public Health Service; she has held leadership positions at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Agriculture and the Alaska Native Medical Center. From 2009 to 2012, she served as the senior officer for environmental health research in the Department of Public Health and Environment at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland.

She is the founding editor of “Pediatric Environmental Health,” a book that has helped train doctors who care for children to recognize, diagnose, treat and prevent childhood illnesses resulting from environmental hazards.

Her pioneering work on secondhand smoke led to nationwide efforts to reduce indoor exposure to tobacco, and resulted from her strong focus on using research to change policy. “It really transformed thinking about tobacco,” says Etzel of the work. “Now anyone can sit in a restaurant or airplane without worrying about breathing someone else’s smoke. Documenting the link between passive smoking and health problems in nonsmokers helped move that thinking along.”

Unfinished business

With those tens of thousands of chemicals in the environment, much work remains to be done, says Etzel. “It’s unfortunate that we don’t routinely test chemicals for potential harm before they are allowed to be released in the environment.” Children, with their extreme sensitivity to these hazards, often suffer first. “Our children should not be the canaries in the coal mine. I think that as a society we can find a better way.”

Today, she says, researchers are making substantial progress in documenting links between chemicals in the environment and their impact on health. “Each generation is smarter about this work and has better tools.” New research, she says, gives “some real evidence to the regulatory agencies and helps change current public attitudes.”

She’s also encouraged by the recent increase in international collaboration on children’s environmental health research. Five countries, for example, are currently working with her to coordinate their studies to assess children’s exposure to certain chemicals in the environment, including some that may be endocrine disruptors. By pooling data, and increasing the number of children studied, researchers can learn more about the links between exposure to chemicals and health issues in children, says Etzel.

In recent years, Etzel has focused on an emerging environmental hazard – exposure to molds in the home. Her research was the first to demonstrate that exposure to toxic molds could be damaging to infants’ health.

Her interest in the harmful effects of secondhand smoke continues, and she also advocates on issues related to nicotine. For example, she wrote an op-ed for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel earlier this year on the dangers of electronic cigarettes to children.

Right now, her own research is focused on the impact of environmental factors in premature births and infant deaths in the Milwaukee area, which fits well with other work at the Zilber School of Public Health.

Etzel was raised in Menomonee Falls and is excited to be back in her home state after 40 years away, and to be part of UWM’s new school of public health.

“It’s extremely exciting to be able to take action to improve the environment in the place where we live. We’re empowering ourselves and others to change our home environment.”

Etzel will be part of a March 13 webinar on children’s environmental health. The event, which is free and open to the public, is part of the Collaborative on Health and the Environment (CHE) Café Call series.

Etzel and Philip J. Landrigan, the other featured speaker and co-editor of the book, will be discussing the book and how it can be used to generate positive action in improving children’s health.

To register for the webinar, which starts at noon Milwaukee time, go to the CHE website, www.healthandenvironment.org/partner