Perched on an aquaculture breakthrough

In a laboratory tank, 8,000 larval fish circle in schools, 18 days old and barely larger than an exclamation point. In another tank, a few thousand fish of the same species, yellow perch, are all grown up, trademark vertical stripes lining their 2-pound bodies. “You hook one of these guys, and you’re taking pictures,” says Osvaldo Jhonatan Sepulveda Villet, an assistant professor in UWM’s School of Freshwater Sciences.

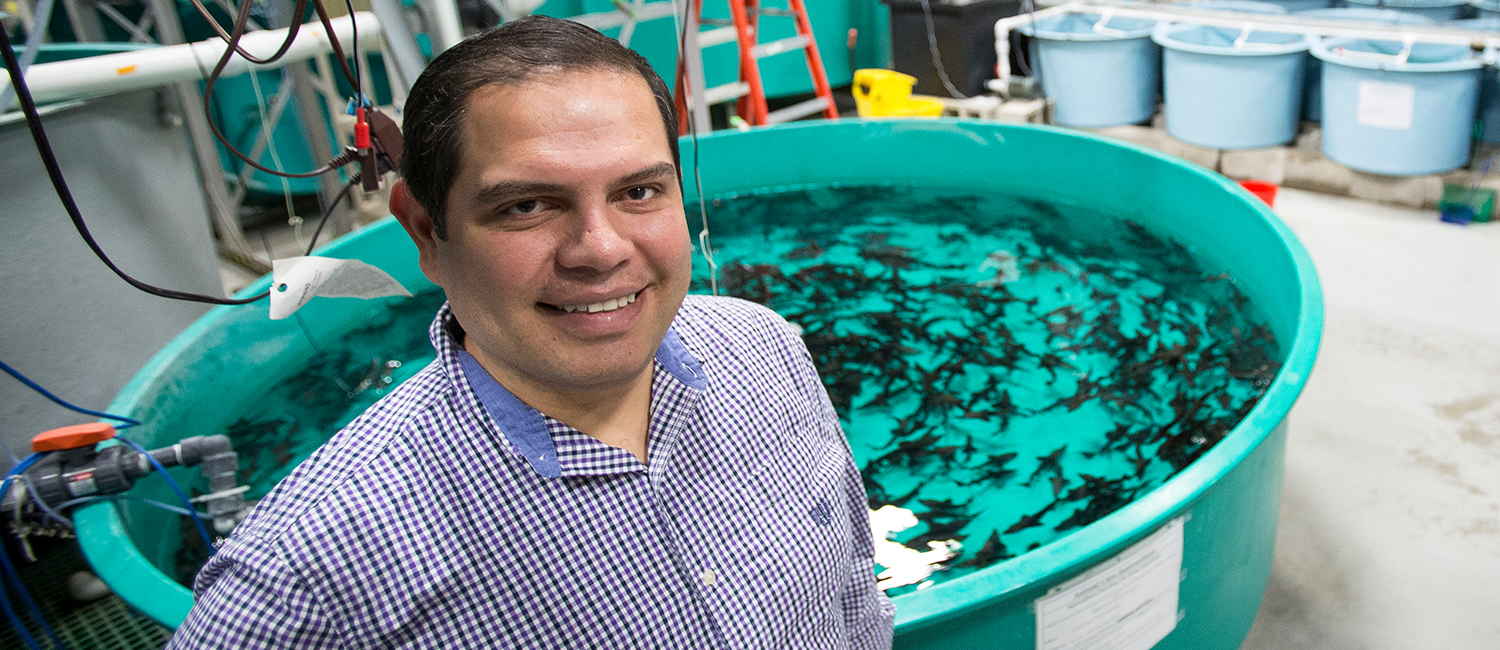

The perch share the Freshwater Sciences lab with other research fish, including a giant tank swarming with baby sturgeon. About as long as a hand, the shark-like black fish skitter sideways across the water’s surface before resuming their leisurely swim. UWM is helping revive the numbers of sturgeon and perch, both of which were once plentiful in the Great Lakes.

Sepulveda Villet’s research focuses on shepherding yellow perch from commas to keepers and restoring the species through aquaculture. His work could have a dramatic commercial impact, too. The United States imports more than 90 percent of its seafood, resulting in a trade deficit of $14 billion in 2016.

Decades of research at UWM, pioneered by Fred Binkowski and now overseen by Sepulveda Villet, has shown massive gains. Up to 40 percent of the yellow perch grown there survive from hatch to market, double the rate of currently operating fish farms. Sepulveda Villet says a 50 percent yield is within reach.

“You’re making it cheaper to produce the fish,” he says.

In the late 1980s, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources surveys in Lake Michigan netted 1,000 perch a night. Now, due to the spread of invasive species, the same surveys yield about 40 a year.

In the wild, just 1 percent of yellow perch survive to market size.

Sepulveda Villet and colleagues implement a multipronged approach involving diet and environment to ensure that more perch grown in tanks survive.

He’s also found success through certain types of selective breeding – encouraging mating of the fastest and biggest females. By the fourth generation, he says, the time to market size shrinks to eight months, down from two years in the wild.