David DiValerio is, by his own admission, a madman. That’s the name — Karma Drondül Nyönpa, or “Karma, Subduer of Beings, Madman” — given him by the Karmapa, the head of the Kagyü sect and arguably the second most important leader of Tibetan Buddhism after the Dalai Lama.

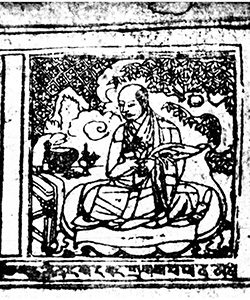

DiValerio, an assistant professor of history and religious studies, has spent the past 15 years studying the history of Tibetan Buddhism. In two recent books — a monograph, “The Holy Madmen of Tibet,” and a translation, “The Life of the Madman of Ü” — he presents a picture that will shock anyone who thinks of Buddhism as a placid, contemplative road to enlightenment.

His subject is the “holy madmen” (“smyon pa,” pronounced nyönpa) of Tibet, with a special focus on three members of the Kagyü sect who were 15th century contemporaries. These men behaved in ways apparently calculated to shock the society they lived in.

One account, written in 1512, describes a madman whose “naked body was rubbed with ashes from a human corpse, daubed with blood, and smeared with fat. He wore the intestines of someone who had died as a necklace.”

For DiValerio, this behavior becomes more interesting when we consider the social context in which these men flourished.

“The ultimate goal of my project is to precipitate a shift in how we think about these figures — shifting from thinking about them as exclusively religious beings to viewing them as motivated by a wider range of concerns,” he says. “To portray them as having normal human relationships,

thoughts, motivations is, in fact, a norm-overturning thing to do.”

DiValerio notes that the Tibetan madmen have counterparts in other religions: the “yurodivy,” or holy fool, in Russian literature; fools for Christ; “intoxicated” saints in Hinduism and Islam.

Tibetans themselves think of the madmen in various ways. Most often their odd behavior is explained as being a manifestation of their enlightenment — their outrageous behavior

would make perfect sense to other enlightened beings. Or perhaps they are trying provoke the rest of us into questioning our “normal” outlook.

But DiValerio takes a very different view.

“To view them in one of these two ways is to view their lifestyle, activities and words as being exclusively ‘religious’ in nature and intent,” he says. “But once we begin to historicize these individual figures, completely new understandings become possible.”

The three most famous holy madmen were born within six years of each other in the 1450s. During that period, Tibet was in the midst of a civil war, and the madmen were being supported by the faction opposing the central government, which was associated with the most conservative sect of Tibetan Buddhism.

“There is a political battle, a religious battle and a broader cultural battle all taking place at the same time,” DiValerio said. “I see the three most famous madmen as arising out of that competitive situation.”

“So, is their ‘mad’ behavior a religious practice?” he asks. “Maybe. But I also argue that it’s very much connected with these real-world, historical issues.”

To the moon or Tibet

DiValerio’s road to his Tibetan studies has a somewhat whimsical beginning.

“My sophomore year of college I saw a flyer for a semester abroad program in India, Nepal and Tibet, and thought I’d like to go somewhere like that — somewhere I couldn’t go otherwise,” he recalled. “I overheard my mom telling a friend over the phone, ‘He can’t go to the moon, so he’s going to Tibet.’ Arriving there really was a jarring and eye-opening experience for me.”

The road to Shambala became the first steps in DiValerio’s path to a career as a Tibetanist. It wasn’t the easiest path.

“About half of what I did in graduate school was study languages: more than four years each of spoken Tibetan, literary Tibetan and Sanskrit. I also spent nine months in Tibet, studying at Tibet University, in Lhasa.

He had the opportunity to see Tibet as few Westerners do.

“I was able to spend a few months traveling to some pretty out-of-the-way places, including living for a month in a monastery. Later, I did nine months of dissertation fieldwork in India. I’ve also done research in Mongolia and Nepal for shorter periods.

“In 2013, I found a copy of the original printing of the “Life of the Madman of Ü,” from 1494 — now preserved on microfilm by the National Archives of Nepal in Kathmandu. This was a major score. Having a copy of the original text significantly enriched my translation.”

DiValerio is now on sabbatical, during which he’ll start work on a book about Tibetan meditation practice.