The aim of managing the world’s large river systems may not necessarily be to sustain them.

Take, for example, an extensive network of dams built along the Amu Darya River in Central Asia during the last 40 years. The dams allowed for cotton irrigation and flood control. But they’re also the reason that the freshwater Aral Sea has shrunk dramatically, leading to a near-collapse of the sea’s ecosystem.

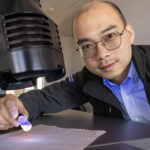

Competing priorities across multiple jurisdictions, economies and cultural traditions may be the toughest barrier in protecting a limited resource that no one can live without, says Tim Ehlinger, an associate professor of biological sciences, who is studying similar challenges to the Danube River in Europe.

“We operate on the premise that if we figure out the scientific issues, we’ll have the magic bullet to a problem,” says Ehlinger. “But it’s only one part of the answer. The human-environment interaction grows out of cultural values, economic pressures and political histories.”

Ehlinger has teamed up with Ryan Holifield, assistant professor of geography, and Manu P. Sobti, associate professor of architecture, to study how consensus on managing water can best be achieved across various kinds of borders – with the hope of informing a model for governing such global resources.

Their project is the first awarded a two-year “Transdisciplinary Challenge” grant from the Center for 21st Century Studies (C21) that is backed by Chancellor Michael Lovell and the Graduate School. The purpose of the annual grant is to encourage collaboration among UWM researchers from disciplines that do not have a history of working together, says C21 Director Richard Grusin.

“We were looking for proposals that were conceived from the beginning as interdisciplinary, rather than projects in which one discipline dominated and the others were ‘added on,’” says Grusin.

“I don’t think it’s an accident that the subject of the winning proposal is water. It’s an issue that involves so many different perspectives.”

Three hot spots

Since taking over C21 at the beginning of this year, Grusin has focused on expanding the reach of the center to include not only the humanities and social sciences, but also hard sciences, math and the professional fields.

“We are interested in how a transdisciplinary approach would change the nature of the questions we ask – not only in science and technology, but also in the humanities and social sciences,” he says.

Ehlinger, Holifield and Sobti’s project includes a comparative study of three vital waterways: The Mississippi River Basin and its artificial route into Lake Michigan in the U.S.; the Amu Darya River that runs along the borders of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Afghanistan in Central Asia; and the Danube River, which cuts through parts of Europe and the Balkans on its way to the Black Sea.

Perhaps the most insight will come from the participation of nine graduate students – two each from biological sciences and geography, and five from architecture.

“Students realize that what they learn often conflicts and there’s something going on in the cracks between disciplines,” says Ehlinger. “Call it a spark that stimulates ideas.”

Lovell, who provided support for the grant, says he has experienced the increased value of an interdisciplinary approach in his own research. “Our initial recipients for this award will be one more example on our campus of how novel partnerships can lead the way to new learning,” he says.

Intertwining interests

Sobti is interested in urbanism and urban histories in Central Asia, especially along the route of the ancient Silk Road.

Those histories affect architecture past and future, and are tied to the Amu Darya, which stretches more than 4,000 miles from the desert in Afghanistan to the Aral Sea. Crossing points on the river were the places where cities sprang up, property became most valuable and people immigrated, all circumstances for potential conflict, says Sobti.

“The three of us were all, in some way, interested in conflict,” he says. “We were looking at these three rivers because the most interesting aspect of each was their connection to risk of conflict. So we’re trying to funnel it in a way that takes a close look at conflict on a single matter across space.”

Just as many pools of knowledge contribute to the physical environment, a broad understanding of individual places is necessary to address conflict across a large expanse. And that is what environmental governance is all about, adds Holifield.

Such information is vital to understanding why issues like protecting Lake Michigan from Asian Carp evade easy solutions.

His team is dissecting the negotiation processes needed to manage for the common good. That includes studying stakeholder participation at the local levels and also the operation of networks of groups with common concerns that operate across large distances.

“The goal is to determine how scale, place and boundaries complicate these processes,” he says.