Desegregation refers to the corrective process of ending racial segregation, and it was typically initiated by court order. During the 1950s and 1960s, segregated institutions in the South fiercely resisted court orders to desegregate. Many African American students, for example, were forced to endure hostile white mobs and resistance from state officials when they began to attend classes at previously all-white schools. Some students even required escorts from federal troops and U.S. Marshalls to safely attend classes.

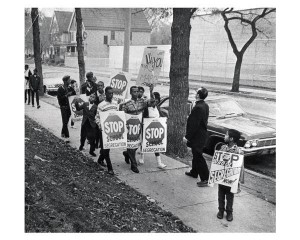

Although Milwaukee school desegregation activists did not face similar mobs, they encountered active opposition to their protests. In 1963, when Wisconsin National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) president and attorney Lloyd Barbee demanded that the state officially acknowledge that Milwaukee schools were segregated, the school board majority refused to accept responsibility for its role in causing segregation, and denied their obligation to correct it. Additionally, many white families began to either flee to the suburbs as the African American population in Milwaukee increased, or utilize a school transfer policy to remove their children from schools with large or growing African American student populations. The failure of government to act led Barbee to organize the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee (MUSIC). After a year of direct-action protests by MUSIC failed to sway the school board in their stance, Barbee filed a federal lawsuit, Amos et al. v. Board of School Directors of the City of Milwaukee, charging the school board with unconstitutionally maintaining segregation in its schools.

In 1976, federal Judge John Reynolds ruled that the school board was guilty of creating and maintaining segregation, and he issued a court order to desegregate Milwaukee’s public schools. The district received national recognition for creating several city-wide specialty schools (also known as magnet schools), designed to attract black and white students from different neighborhoods. At the same time, a voluntary metropolitan desegregation plan known as the Chapter 220 Program permitted city-suburban student transfers. In the late 1970s, a second round of protest erupted as some civil rights activists questioned whether the implementation of school desegregation placed a disproportionate burden on the African American community, particularly at North Division High School. LW